24 Jun Blog: Black Lives Matter and Moluccan anti-racism

By Fridus Steijlen. The original blog is the column ‘Black Lives Matter en Moluks anti-racisme’ in the newsletter of Museum Maluku, written in Dutch.

The Black Lives Matter protest held on 10 June 2020 was originally planned to take place at Anton de Komplein in the Zuidoost district of Amsterdam. But due to the huge numbers expected to attend, the demo was moved to the nearby Nelson Mandelapark, which is larger. Local news station AT5 covered the event live. In total, 11,000 people turned out to call for equality and to demonstrate against racial profiling and police brutality, all while keeping the prescribed 1.5 metres apart and wearing face masks. In the distance, somewhere in the crowd, I noticed two RMS flags being waved. They were being used as a sign of solidarity and also to state that Moluccans are against racism. The flags did not look out of place; earlier on I had seen ‘Black is beautiful’ written on the wall below a statue of Anton de Kom.

To me, this slogan served as a missing link. Protests in the Netherlands and the rest of the world had ignited following the death of George Floyd in the United States on 25 May 2020. Inspiration for these demonstrations had come from protests in America. This was something I had seen in Dutch history before, or in Moluccan history to be more precise. And then, too, discrimination had been involved.

Black is beautiful

Towards the end of the 1960s, there were increasingly frequent encounters between young, second-generation Moluccans and Dutch society. People having been moved from camps to residential areas was one of the reasons for this. Young Moluccans found that they were viewed as inferior in Dutch society and that they were discriminated against. What followed was a kind of collective response. Young Moluccans were inspired by the ‘black is beautiful’ and black power movement in the United States. Through these American movements, they learned to be proud of and stand up for themselves.

This resulted in confrontations with white Dutch youths. In the late 1960s, there were clashes between the two groups when young Moluccans travelled throughout the country en masse, taking advantage of the special Tienertour rover tickets. Things became so bad that Pastor Metiary, who at that time was the chair of the largest Moluccan organization in the country, felt the need to distribute pamphlets, urging young Moluccans to refrain from engaging in confrontations. There was a link to the American black movement through a number of Moluccan youths who were in contact with progressive Dutch movements, such as the Vrijheidsfilms cinema club. This was also the link that contributed to the wave of radicalization culminating in the action taken in the 1970s.

‘But there were also movements challenging racism and protesting against it. Moluccans were a part of these’.

But let’s get back to discussing the stance on racism. In the 1980s, it became increasingly clear that the Netherlands had become a multicultural society and that the government was keen to pursue a ‘general minorities policy’. That institutional and daily racism was in evidence was also already clear. How subtle that racism was in practice was expressed in robust terms by Philomena Essed in her book ‘Alledaags Racisme’ (Everyday Racism, published in 1984. This did not make her many friends. Plenty of people denied that racism existed back then too. But there were also movements challenging racism and protesting against it. Moluccans were a part of these. They were involved in the annual commemorations of the racist murder of the Antillean Kerwin Duinmeyer in 1983. They attended the Princenhof conference against discrimination and racism in Amsterdam in January 1984. And in 1985, Moluccans from Twente organized a bicycle ride to Amsterdam as part of the ‘Ne pas touche mon pote’ (Don’t touch my buddy) campaign. This coincided with the visit of French organization SOS-Racisme (founded in 1984) to the Netherlands. There were anti-racism agencies in the Netherlands which, just like SOS-Racisme, used research to establish racism and recorded racist and discriminatory incidents. And ‘Anti-Discrimination Councils’ at both national and regional level came into being in the second half of the 1980s. Moluccans were also active participants in these agencies and councils. One such organization working at a national level was the Inspraakorgaan Welzijn Molukkers (Consultative Body for the Welfare of Moluccans, or IWM).

Moluccans were actively involved in anti-racism initiatives and projects in the 1990s too. The Werkgroep Discriminatie Molukkers (Discrimination Against Moluccans Working Group) was formed by Moluccans from various districts in 1992/1993. And in 1995, a notable project initiated by two Irish-Jewish girls was implemented: six European Youth Trains set off from different corners of Europe, destined for the European Parliament in Strasbourg, where the young people on board spent one week. This was a campaign against racism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism and intolerance. Each train was assigned a theme and young people were picked up at 42 stations along the various routes. The leader on one of these trains was a Moluccan. Moluccan representatives had also participated in similar European campaigns in preceding years.

Racism has not gone away

For some reason, things quietened down on the anti-racism and anti-discrimination front at the beginning of this century. But that did not mean that racism and discrimination had gone away. Far from it. Fortunately, new initiatives have emerged, at least over recent years, one of these being the Kick Out Black Pete campaign. I have seen Moluccan faces involved in this too. The movement now emerging seems to be stronger than the one in the eighties and nineties. To some extent, the demands are the same, but they are now being made on a much larger and broader scale. In them, echoes of the movements of the 1960s can be heard. This is a good thing and it offers encouragement.

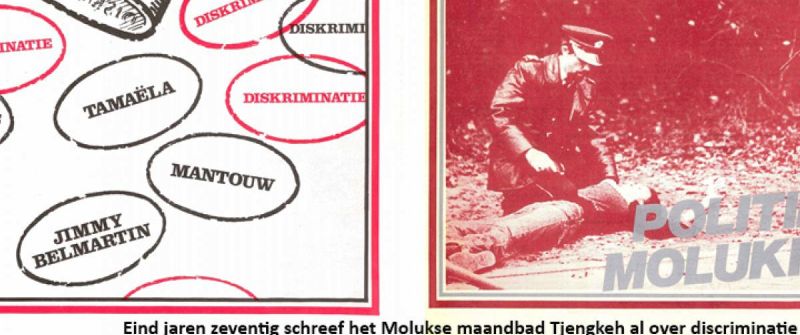

Cover photo: Front page of the Tjengkeh magazine from the 1980s.

(Fridus Steijlen is Professor Extraordinary ‘Moluccan Migration and Culture in a comparative perspective‘ at the Faculty of Social Sciences of the VU University, Amsterdam, and senior researcher at KITLV. He is working on postcolonial migration from Indonesia and daily life in present day Indonesia.)

Adriaan Bedner

Posted at 13:36h, 26 JuneNot only were Moluccans waving RMS-flags, among those addressing the crowd was also a Moluccan. I found it great to see how this demonstration united people withall kinds of migrant histories – and fortunately also a with non-migrant backgrounds.