07 Jun Blog: Celebrating Ramadan in Style?

The fasting month in Indonesia comes with new gadgets and ‘special offers’ advertisements. Chris Chaplin wonders whether or not this affects the pious character of fasting.

On the 6th June the majority of Muslims across the world welcomed the start of the fasting month of Ramadan. In Indonesia, the Religious Affairs Ministry as well as Indonesia’s two largest Islamic organisations, Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, all confirmed that the slender crescent (hilal) was sighted on Sunday to mark a new moon. As months in the Muslim calendar are lunar, a new moon marks the beginning of a new month.

To those familiar with Indonesia, the fasting month is filled with unique events, sites and sounds. Days can somehow feel slower and the nights more festive. Mosque loudspeakers become more active. Posters of notables and politicians donning Islamic dress and displays of Islamic mosaic designs are common. Just before dusk, street vendors begin setting up stalls to sell special treats to breakfast, such as Kolak – a think and sweet syrup drink made with banana and sweet potato.

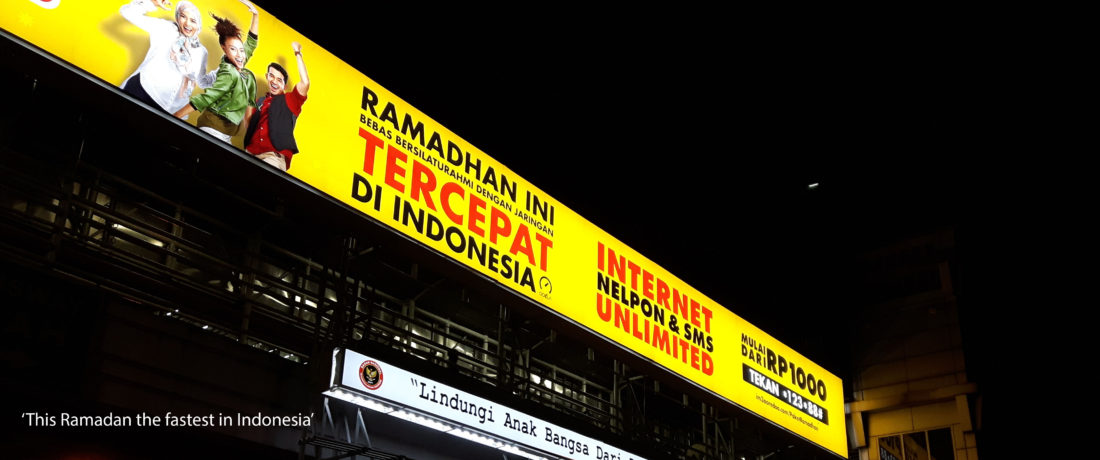

Ramadan has also increasingly been characterised by the promotion of a market for Islamic goods and TV programs. Mobile phone companies offer special Ramadan packages, shopping malls put up special decorations for the month. Furthermore, in the week before Ramadan this year the Jakarta Convention Center held the ‘Hijab for the World’ fashion show, where companies such as Elhijab presented their Ramadan 2016 collections.

Yet have such practices led to a weakening of faith and tradition? Indeed, several preachers question whether the month has lost its spiritual meaning and become a commercialised event with little benefit to the umma (religious community). And they may have a point; non-Muslim vendors and companies can easily benefit from these sales. For instance, in Jakarta the Plaza Indonesia shopping centre – which is filled with boutique global brands such as Gucci and Armani – held a two-day pre-Ramadan late night shopping event.

However, equating the commercial use of Ramadan with a more shallow level of piety is misleading. Religious commodities have become a visible part of Indonesian consumer society – but they represent an attempt to synthesise Islamic expression and the strengthening of the urban Muslim Middle Classes. Pious and observant, these individuals see their faith not solely through the prism of Islamic tradition but as part of a cosmopolitan, intellectual (and often capitalist) modern society. Such consumption is part of a bigger picture that includes a growing industry of Islamic charities, philanthropy and education is as much part of this trend as is Islamic fashion.

The finer points concerning exactly how one celebrates and observes Ramadan are not confined to a pre-defined formula. Muslims often disagree as to when the month of Ramadan begins, given that Nadhlatul Ulama calculate the start of the month by sighting the new moon (rukyat) while Muhammadiyah calculate its arrival through astronomical charts (hisab). Such differences may symbolise one’s adherence to a specific organisation, but like the use of new religious products, does not undermine the deeply personal nature of Islamic belief. Rather, such diverse opinions, events and symbols form part of the rich character that marks the fasting month in Indonesia.

(Chris Chaplin is a postdoc researcher at KITLV focusing on the study of conservative Islamic movements in Indonesian society and their influence on ideas of citizenship and class.)

No Comments